Before the Easter Sunday attacks in Sri Lanka, it was almost unthinkable that the Islamic State (ISIS), under the leadership of Mohamed Zahran Hashim from Kattankudy, could coordinate such a devastating act. The Easter Sunday bombings stand as one of the deadliest terrorist attacks globally since 9/11. Overlooking the risk of anti-Semitism gaining ground in Sri Lanka may lead to dire outcomes. The recent controversy following the return of a group of Sri Lankan journalists from Israel highlights that anti-Semitic sentiment is beginning to influence local politics.

Pro-Palestinian activism in Sri Lanka has increasingly provided fertile ground for anti-Semitic sentiment. What often goes unnoticed is that, in practice, advocacy for the Palestinian cause has become closely linked with support for Hamas. Therefore, the emergence of anti-Semitism in Sri Lanka should be interpreted as an ideological endorsement of global Islamic extremism. Critics of this perspective tend to deflect it as Islamophobia, insisting, “There is no anti-Semitism in Sri Lanka because Sri Lankans cannot be anti-Semites; anti-Semitism is rooted in Europe’s perception of Jews as a religious, cultural, and political other.” If that’s the case, how do we account for the opposition to the Chabad House and the Jewish presence in Sri Lanka?

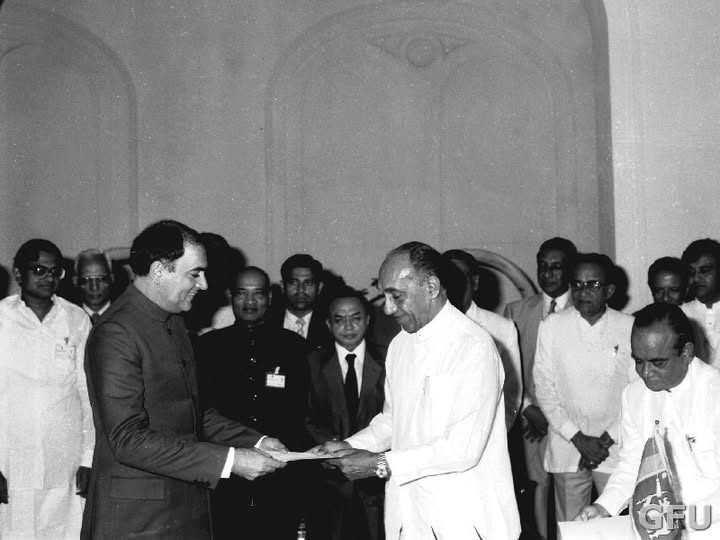

It is not new for Sri Lanka’s main political parties to use historical support for Palestine as a political stance, even though the country recognized the state of Israel on March 25, 1949. The exception was under J.R. Jayewardene, who sought closer ties with Israel and supported opening an Israeli interest section in Colombo. Given this history—marked by fluctuating relations—pro-Palestinian sentiment has become a political trend among mainstream parties, including Tamil minority parties. Against this backdrop, Colombo has always approached close cooperation with Israel hesitantly. The National People’s Power government also shares this reluctance. The crucial question remains: do Sri Lanka’s strategic thinkers realize that the current Gaza conflict cannot be addressed with the same approach as previous support for PLO-led Palestine under the banner of non-alignment?

In this context, a political directive—promoted by Muslim politicians and groups in Sri Lanka—demands that everyone support Palestine. Those who refuse are often labeled as Mossad agents. For example, comments made by a Muslim member of parliament targeting journalists who returned from Israel show how anti-Semitic narratives are slowly taking shape, frequently by spotlighting Israeli tourists. Traditionally, anti-Semitism has involved limiting the participation of Jewish people in society.

Two groups are central to this trend: some Muslim politicians and individuals from the Eastern Province actively promote these campaigns, while opposition parties—especially Muslim politicians—also participate, seeking to challenge the ruling National People’s Power government. A fabricated story about the “occupation” of Arugam Bay, a major tourist destination, by Jewish people is being spread in a manner reminiscent of Goebbels’ propaganda. This is clear evidence that seeds of anti-Semitism are being sown in Sri Lankan local politics.

Muslim political groups and the old left, who vocally condemn the situation in Gaza, did not acknowledge or condemn the inhumane attack on the Jewish people on October 7, 2023. On that day, more than 1,200 men, women, and children—including 46 Americans and citizens of over 30 countries—were brutally killed by Hamas in the largest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. Even the religious leader of Saudi Arabia condemned the October attack, yet the Muslims in Sri Lanka did not. Sheikh Mohammed Al-Issa—a former Saudi Justice Minister who now serves as Secretary General of the Muslim World League (MWL), the largest non-governmental Islamic organization in the world— called Hamas a terrorist group and referred to the October 7th attack as a crime. In his remarks in Washington, D.C., he added, “We want the war in Gaza to end and all the hostages to be freed.” What was the stance of Sri Lanka’s Muslim political elite and religious leaders?

However, Muslim Congress leader Rauff Hakeem condemned Israel’s “Operation Rising Lion” against Iran, labeling it a “burial action” and accusing Prime Minister Netanyahu of being the “head of a genocidal team” trying to destabilize the Middle East. Notably, no Muslim country in the Middle East supported Iran during this incident. After Israel’s attack on the safe house where Hamas leaders sheltered in Qatar, Hakeem criticized the NPP government for “tactical or strategic collusion” with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his administration. Yet, he still has not condemned Hamas’s terror against Jewish people. If this is not hatred of Jews, then what is it?

Based on this author’s observations during a recent visit to Israel—including a visit to the site of the October 7 massacre at the desert festival near Kibbutz Re’im in the western Negev, where thousands had gathered—there is a palpable sense within Israel of an obligation to prevent such tragedies from happening again. This sentiment underpins the rationale behind the current Israeli military campaign to eliminate Hamas. While it is undeniable that civilian casualties are occurring in Gaza, as one retired Israeli military officer remarked, “War is ugly, and its consequences are troubling.” Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that the ongoing conflict has its roots in the chain of violence that began with the events of October 7.

In this context, the ongoing conflict is not a war that Israel chose, but one that has been forced upon it by Hamas. However, in Sri Lanka, discussions about Gaza rarely consider this perspective. Instead, they consistently reflect an anti-Israeli sentiment. If we examine the situation closely, it becomes clear that the pro-Palestinian narrative, along with its discourse, works to weaken the relationship between Israel and Sri Lanka—a goal actively pursued by certain Muslim politicians. For this reason, the author identifies these developments as the onset of anti-Semitism. In political terms, anti-Semitism, anti-Jewish, and anti-Israel sentiments are inseparable; they function as a single ideology.