In the wake of the recent U.S. tariff relief for Colombo, the U.S. Navy’s littoral combat ship USS Santa Barbara (LCS 32) made a port call at Colombo from August 16 to 21. This visit coincided with the arrival of the Indian Navy’s INS Jyoti (Fleet Tanker) and INS Rana (Destroyer), both in Sri Lanka to participate in the 12th edition of the annual bilateral maritime exercise, SLINEX-2025, between the Indian Navy (IN) and the Sri Lanka Navy (SLN).

U.S. Ambassador to Sri Lanka Julie Chung described the arrival of the USS Santa Barbara as a powerful symbol of the U.S.–Sri Lanka partnership in action. “As part of the U.S. 7th Fleet—the Navy’s largest forward-deployed fleet—this visit reflects our shared commitment to maritime security, regional stability, and a free and open Indo-Pacific,” she said.

The USS Santa Barbara is an Independence-variant Littoral Combat Ship designed for operations in near-shore environments, supporting forward presence, maritime security, sea control, and deterrence missions. Christened on October 16, 2021, it now operates as part of Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 7, conducting regular patrols in the Indo-Pacific to deter aggression, strengthen alliances, and advance future warfighting capabilities.

Amid these developments, questions linger about how a possible Trump 2.0 administration might approach Sri Lanka. The answer is far from clear. During Trump’s first term, U.S.–Sri Lanka relations faced challenges, particularly under Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s leadership. Notably, during his 2020 visit to Colombo, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo voiced strong concerns about China’s expanding influence in the region, describing the Chinese Communist Party as a “predator” in Sri Lanka and asserting, “We see from bad deals, violations of sovereignty, and lawlessness on land and sea. The United States comes in a different way—as a friend and partner.” Against this backdrop, the trajectory of U.S. policy toward Sri Lanka under a renewed Trump presidency remains uncertain, especially as the political landscape in Colombo continues to evolve.

Despite objections from both India and the U.S., the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration permitted the Chinese survey vessel—widely regarded as a spy ship—Yuan Wang 5 to dock at Hambantota Port in 2022. This episode, together with the 2014 docking of Chinese nuclear submarines in Colombo under then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa—without prior notification to New Delhi—has sparked ongoing debate over the nature and extent of Chinese maritime activity in Sri Lankan waters.

India has consistently conveyed its security concerns regarding any perceived increase in Chinese naval presence in the region. In response, President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government introduced a yearlong moratorium on foreign research vessels entering Sri Lankan waters, reflecting Colombo’s efforts to address regional sensitivities.

Under the NPP government, Colombo presently welcomes warships from a range of countries to its ports, while maintaining restrictions on the entry of Chinese research vessels into its territorial waters—though without officially declaring a moratorium. This selective policy has already drawn criticism from Beijing, which has described Colombo’s stance as the result of “third-party interference” in decisions regarding Chinese research vessels.

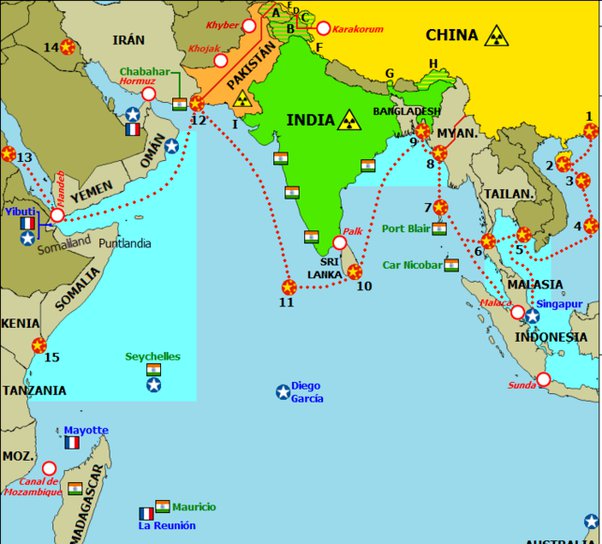

Against this backdrop, how Colombo chooses to navigate this delicate situation remains to be seen. China is unlikely to remain silent and will likely continue pressuring Colombo to adopt a neutral policy regarding the entry of all foreign warships. Since taking office, the NPP government has considered developing a comprehensive standard operating procedure for permitting foreign research vessels, but this policy has yet to be finalized. As noted in a July 2025 article by this author, “If Sri Lanka is sincerely committed to establishing standard procedures for foreign research vessels, it may benefit from drawing on Indian expertise, given its current limitations in evaluating the technical aspects of Chinese survey ships.”

Ultimately, Sri Lanka’s close proximity to India and the complex security environment of the Indian Ocean mean that any standard operating procedure will have to address not only regulatory fairness but also the persistent concerns about covert activities. Even the most robust procedures may not fully allay apprehensions about foreign military or intelligence operations in the region. Any procedure that does not consider India’s concerns is unlikely to be accepted as a true standard.