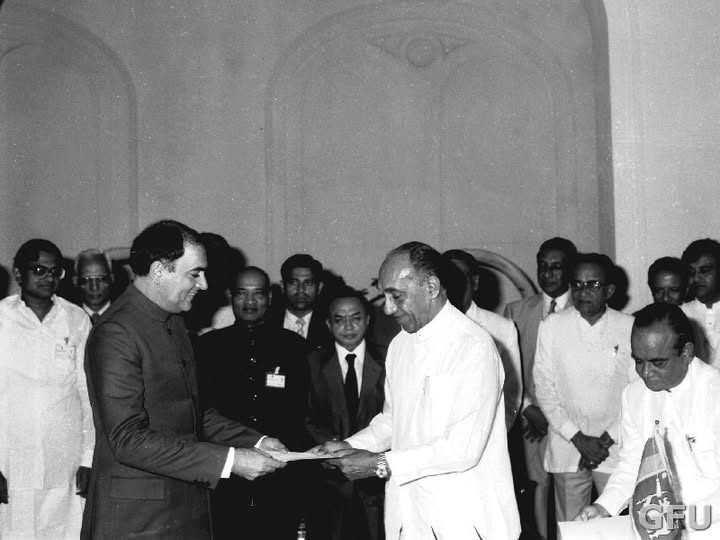

Even after thirty-eight years, the Indo-Lanka Accord, signed on July 29, 1987, stands out as a remarkable event in Sri Lanka’s history. After much struggle, the accord led to the 13th Amendment to the constitution, which introduced a provincial council structure in an attempt to resolve the island’s protracted ethnic conflict. From the outset, hardliners on both sides rejected the 13th Amendment as a comprehensive solution: Tamil hardliners argued it was insufficient, while some Sinhalese hardliners believed it gave too much to the Tamils.

To this day, Sri Lanka’s ethnic question remains unresolved, stubbornly echoing those same old arguments—even though the bloody civil war ended with the loss of thousands of lives. History remains our only teacher, reminding us of what we failed to understand in the past. Despite India’s hard-footed Cold War approach, she put her best efforts into helping Sri Lanka move forward, but both factions failed to engage constructively.

If we examine the post-Indo-Lanka Accord era, it is clear that successive governments of Sri Lanka have failed to show even a little progress. Sixteen years after the end of the war, the nation still struggles to move an inch toward resolving the national question beyond the 13th Amendment.

Throughout my political journey as an opinion maker, I have often observed—especially on the Tamil side—a tendency to blame India, a sentiment that persists even today. Whenever I hear such statements, I am reminded of the African proverb: “He who spits against the sky, it falls on his face.” Blaming powerful countries will not affect them; it always rebounds on those who blame.

Amidst a world entangled in Cold War tensions, India inevitably took a tough stand on Sri Lanka after President J.R. Jayewardene shifted away from the non-aligned orbit. Had Jayewardene acted in accordance with India’s concerns, India would never have decided to train Tamil militants. At that time, as a nation within the Soviet sphere of influence, India faced difficult choices to maintain its regional power status.

In Sri Lanka, many still cling to old hatreds, missing the reality: if India had truly wanted to break up Sri Lanka, it could have done so through Tamil militants, just as it did in East Pakistan. However, from the beginning, India had a firm policy not to support a separate Tamil state. Gopalaswami Parthasarathi, then special envoy of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to Sri Lanka, made it clear to all militant leaders that India would not support a separate state—and would never allow it.

When I interviewed the late R. Sampanthan, leader of the Tamil National Alliance, in 2010 about the Vattukottai Declaration of 1976—why S.J.V. Chelvanayakam made that decision and whether it was wise to call for a separate state without knowing how to achieve it—Sampanthan replied boldly, “If it was needed by India, it would have happened.” Even today, some manipulate the same narrative, suggesting India supports Tamil separatists or controls the north and east when it comes to investments in those provinces. But the reality is far from that.

India devoted maximum effort to move the nation forward, but both the LTTE and the Premadasa-led UNP missed the bus. Both Premadasa and Prabhakaran wanted India out for their own political survival. Later, LTTE ideologue Anton Balasingham admitted the truth: the LTTE compromised with Premadasa because, as he stated, “We were on the brink of destruction; the IPKF had taken the entire north and east—so we entered into an understanding with Premadasa to escape total annihilation.”

If we are truly committed to learning from history, a crucial question arises: who was ultimately responsible for empowering the LTTE as a powerful non-state actor—Premadasa’s UNP or India?

Premadasa and Prabhakaran invested in each other against India. As a consequence of this dangerous game, Premadasa lost his life within a few years, and Prabhakaran and his entire force were destroyed at Mullivaikkal. What was achieved by antagonizing the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord? Nothing.

The reality is that the ethnic question remains unresolved. If we truly saw it as a domestic issue, why have we not found a solution better than the 13th Amendment? If it is not the optimal solution, successive Sri Lankan governments could have proposed another—but this has not happened. What does this teach us? The answer is that the provincial councils introduced by the Indo-Lanka Accord remain the best option for Sri Lanka to close its internal ethnic gap and move forward.

Looking through the lens of history, India’s involvement in Sri Lanka has been that of a “bridge, not a battering ram”—from the infamous “Parippu Drop” of June 1987 to providing $4 billion in aid during Sri Lanka’s recent economic crisis. In this context, this essay argues that we all missed the bus—and, worryingly, we are still in danger of missing it again. There were historic opportunities during the so-called government of good governance led by Maithripala Sirisena, but they missed the bus. Now, with the National People’s Power government holding a rare majority in parliament, the opportunity is here again.