There are many perspectives on U.S. tariff policy. Some describe it as “mercantile diplomacy”—a strategy that prioritises tariffs and economic sanctions to discipline competitors, especially China. Canadian Prime Minister Marconi calls this an attempt to “monetize America’s hegemony.” Former Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe has warned that high reciprocal tariffs could severely harm Asia’s manufacturing base, pushing regional support even closer to China. Leaders worldwide have voiced different perspectives, each coloured by their own political understanding. Yet, as Emmanuel Wallerstein reminds us: “Who will win in all of this and what will happen to the system—I do not know, you do not know, we do not know.” The situation totally unpredictable.

Beyond these debates, the reality is stark. When the United States, the world’s foremost power, makes a strategic decision, other countries face two choices: align or oppose. As a vulnerable nation, Sri Lanka cannot even imagine opposing such a decision. The pragmatic approach is to engage with the U.S. while also nurturing economic and strategic partnerships with India.

Recent reports note that during U.S. tariff negotiations, American authorities proposed restrictive measures on trading with China. However, these were rejected by Sri Lanka’s National People’s Power (NPP) government, which declined to comply in principle, in line with its neutral foreign policy, sources added.

This reveals that U.S. tariffs are part of a broader strategy to contain China. Meanwhile, Colombo continues to negotiate for a reduction of U.S. tariffs to 20 percent. Yet, beneath these talks lies a critical question: Can Sri Lanka meet U.S. expectations? If not, why should Washington offer concessions?

At the same time, news broke that Sri Lanka reaffirmed its strategic cooperation with China, expressing readiness to further strengthen ties in trade, investment, infrastructure development, and maritime affairs, on the sidelines of the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meetings in Kuala Lumpur—a move contrary to U.S. expectations. This underscores the country’s ongoing struggle with an inconsistent and faltering foreign policy—a fundamental flaw at the heart of its international relations.

It may seem logical to believe that sound economic policy alone will lift Sri Lanka out of crisis. But the deeper issue is a lack of coherent foreign policy. Without strategic direction, any gains will be temporary, and lasting progress will remain out of reach.

The imposition of U.S. tariffs is unwelcome news for a nation striving to recover. The reduction in the initial rate is a relief, but the journey to economic recovery will be anything but straightforward. If these hurdles persist, the NPP government could face the same pressures and public discontent that toppled Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

When Sri Lanka fell into bankruptcy, one truth became clear: Even though Sri Lanka claims to be a true friend to many, no other country acted as a true friend during the historic economic crisis—except India. India provided over USD $4 billion in assistance without any preconditions—significantly more than the International Monetary Fund’s 48-month bailout of about USD $3 billion. Now, India has extended a $1 billion credit line for Sri Lanka by one year.

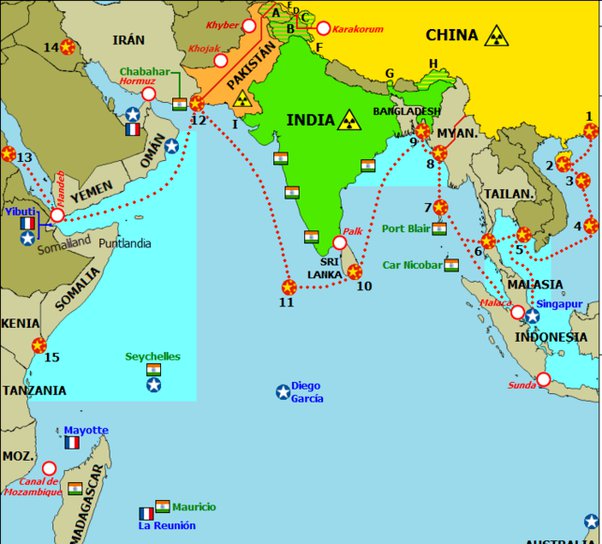

Given these realities, Sri Lanka’s path to stability must be built in close collaboration with India. This is more than an economic necessity; it is a strategic recalibration. Working with India also brings Sri Lanka closer to meeting U.S. expectations while balancing regional interests.

The current approach of the United States signals the beginning of a new order. As experts have pointed out, according to U.S. foreign policy, there will be no return to the pre-Trump era. In this context, Sri Lanka should consider how to adopt a policy stance that will allow it to survive in any situation. Colombo’s usual neutral, non-aligned rhetoric may no longer be beneficial

India, now the world’s fourth-largest economy and an emerging global power, presents Sri Lanka with unprecedented opportunities. As India’s immediate neighbour, Sri Lanka is uniquely positioned to benefit. But the question remains: Is Sri Lanka truly grasping this opportunity?

There are roadmaps for deeper connectivity—maritime, air, energy, trade, and people-to-people—that have already been articulated and are on the table. In July 2023, then-President Wickremesinghe and Prime Minister Narendra Modi outlined a framework for cooperation. The new government under Anura Kumara Dissanayake has agreed in principle, but progress has been slow. The NPP government must prioritise negotiations to implement these initiatives, especially the Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ETCA), which should be finalised without delay. Strategic projects should move forward with a fast-track approach—such as the Trincomalee tank farm, Kankesanthurai fort, the multi-product petroleum pipeline project, and the land bridge across the Palk Strait—described as “GameChangers” by India’s ambassador—which offer genuine hope for Sri Lanka’s economic transformation.

If Colombo remains shackled by outdated anxieties about “big brother” dominance, any talk of economic stability will remain empty rhetoric. Continued vulnerability and the shadow of bankruptcy will persist. Concerns that increasing trade volume could make Sri Lanka a peripheral unit of the Indian economy and lead to a loss of autonomy are overstated and only deepen Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. When the country was in a state of bankruptcy, nationalist rhetoric offered no solutions—only pragmatic cooperation and clear strategy can deliver results.