As Sri Lanka grapples with uncertainty over the long-delayed provincial council elections, a fresh argument has surfaced in the political arena. Former Member of Parliament and General Secretary of the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK), M.A. Sumanthiran, has raised suspicions that the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) may be considering a path that aligns the country with China’s governing model. His remarks, delivered during a recent interview with a private television channel in Jaffna, have intensified discussion about the future direction of Sri Lanka’s political landscape.

Sumanthiran raised this concern based on the response expressed by the President during a recent meeting with him. According to him, the President said a solution would be provided but did not specify what it would be. This has created suspicion, because so far the Western model of power sharing has been the framework long considered and we have examined the issues but none of those efforts have been successful. Why keep talking about something that failed? This seems to be the President’s view. For us, the Chinese model or any other system is not a problem — whatever the system, it is right if we have power in our hands,” Sumanthiran stated.

As he observed, is the JVP-led National People’s Power truly contemplating the adoption of a Chinese-style system of governance? Could this be the reason Tilvin Silva dismisses Sri Lanka’s Provincial Council framework as a failed experiment? Sumanthiran’s remarks inevitably thrust these critical questions into the spotlight. After all, interpreting governance through the lens of the Chinese model stands in stark contrast to the Indian model of power sharing.

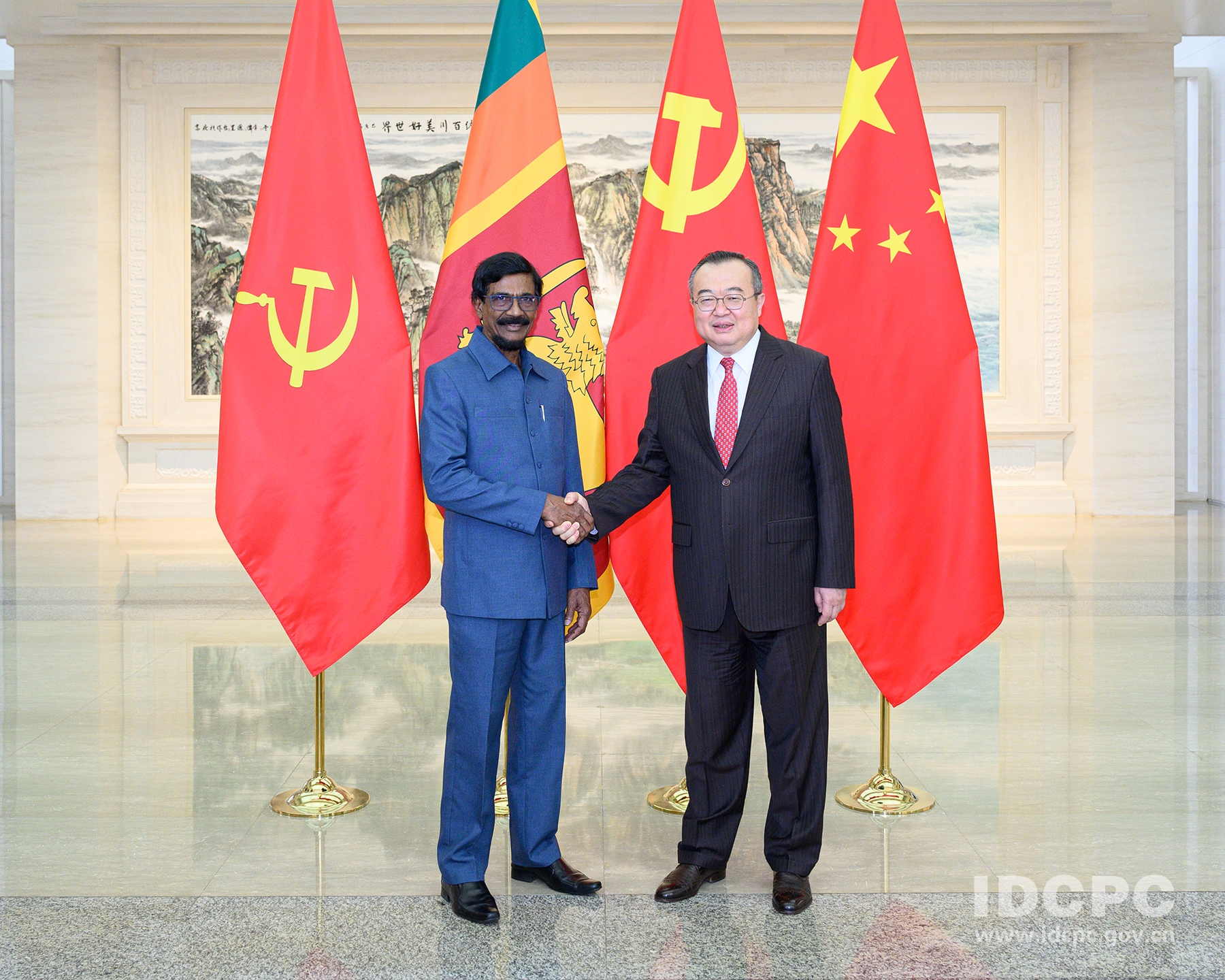

The attraction to the Chinese system of governance is not new in Sri Lankan politics. During the Rajapaksa era, headlines highlighted the close ties between the ruling parties of China and Sri Lanka, which were committed to regular exchanges and in-depth sharing of governance experiences. If Gotabaya Rajapaksa had remained in power, it is unclear what would have happened, as he was serious about introducing a new constitution. The main purpose of that constitution was to abolish the 13th Amendment — introduced due to Indian peacekeeping intervention — and replace it with district councils.

The JVP’s background is distinct from other ruling elites who have led the nation. While now presenting a different political face, the movement’s past was rooted in anti-Indian rhetoric and opposition to India’s peace initiatives in 1987, which produced the Indo-Lanka Accord. That accord is seen as the only successful effort to address Sri Lanka’s ethnic question, as it created the provincial council system modeled on India’s framework.

Tilvin Silva, the powerful JVP secretary, still echoes the party’s earlier position. He argues that the “Provincial Council system is a failed system which is of no use at all. Yet, we would not abolish the Provincial Council system without presenting an alternative viable solution,” though he has not yet revealed what that viable solution would be. Since entering the democratic mainstream in 1994, the JVP has claimed to have a solution, but the nature of that proposal remains unclear. In 2013, JVP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake stated: “We decided that as a party opposing the PC system, we should draft our proposals and publicize them because we do not believe that either extreme would offer an effective solution.”

Against this backdrop, the question of whether the JVP has China’s political system in mind, as Sumanthiran suggests, cannot be easily dismissed.

During the peak of China’s influence in Sri Lanka under the Rajapaksa clan, Professor Patrick Mendis argued that “the ancient Buddhist Island is pivotal to the master plan of the 2049 centennial goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the completion of its great rejuvenation.” Even though the situation changed after the fall of the Rajapaksas, it is difficult to predict the future direction of Colombo’s foreign policy, especially with the JVP — Sri Lanka’s only major Marxist party — now in power.

Despite expectations that the JVP would move in a pro-Chinese direction after coming to power, not shown such moves so far. Instead, there has been moderation. China’s wolf warrior moves of the Rajapaksa era, also seem to have faced setbacks. Meanwhile, global politics is shifting, with regional hegemony once again becoming visible. In this context, will the JVP attempt to sever India’s long-standing engagement with Sri Lankan Tamils?

While it is true that attempts at a state-based solution to Sri Lanka’s ethnic problem have not succeeded, it is also true that the 13th Amendment to the Constitution through the Indo-Lanka Accord was a significant step forward. However, Sri Lanka’s ruling elites have failed to fully implement it, making it appear unsuccessful. In reality, the Provincial Council system is not inherently a failed system, but one deliberately undermined. Mistakes have also been made on the Tamil side.

It is against this background that discussions on what system is appropriate for Sri Lanka’s ethnic problem continue. Can the Chinese system truly be an option for a country struggling with ethnic divisions?

How minorities are treated within China remains largely opaque. Fundamentally, China is a Communist Party-led state tasked with “exercis[ing] overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country.” Independent studies show that the CCP fears that a federal structure would divide the country. Although the Han ethnic group accounts for about 90 percent of China’s population, roughly 125 million people belong to 56 constitutionally recognized minority nationalities, each with distinct cultures, languages, and geographic bases. To manage this diversity, China has designated five national so-called “autonomous regions” and numerous lower-level autonomous areas, where minority groups are formally guaranteed representation, employment opportunities, and language rights. In practice, however, the state has redrawn administrative boundaries and encouraged Han migration, measures that have diluted minority political influence and cultural identity.

China’s long-term goal must be understood alongside CCP ideology: to eliminate cultural differences among minorities through “ethnic fusion” and create one unified Chinese people. New corps of conservative CCP theorists have urged the adoption of a “second-generation policy toward nationalities.” This is a “melting pot” strategy — meaning “pushing ahead with the integration of nationalities.” According to Xi, all nationalities must “firmly cast a consciousness of commonality among the Chinese people, so that different ethnic minorities can tightly embrace each other like pomegranate seeds.”

The JVP’s Marxist-inspired approaches have shifted over time — from the era of its founder Rohana Wijeweera, when the party strongly opposed devolution, to its current leadership under Anura Kumara Dissanayake. It remains uncertain whether this new political face has been influenced by the movement’s foundational DNA. Still, by persisting in its claim that the Provincial Council system is a failure, doubts linger over whether the JVP has truly moved beyond its earlier, contradictory stance on power sharing for the Tamil people — and what alternative solution, if any, it envisions.